EXPLAINER | Zambia’s K21 Billion Bond Rush: What It Means, and Why It Matters

One of the most important economic stories in Zambia this month did not come from Parliament or a political rally. It came quietly from the Bank of Zambia’s latest Government bond auction, where demand reached historic levels.

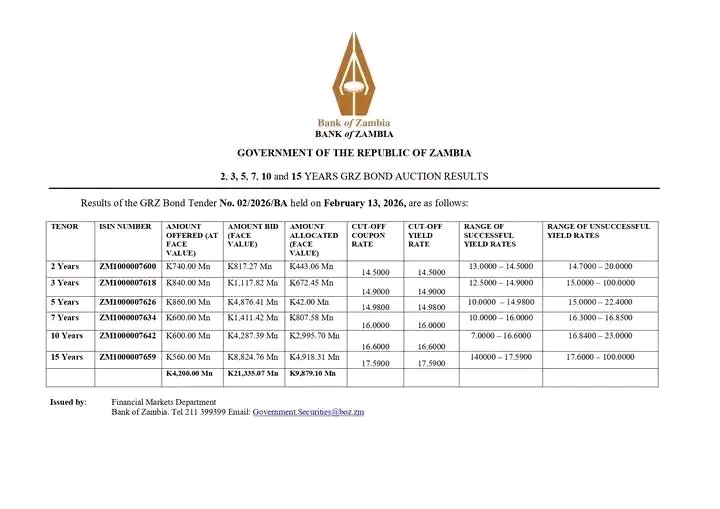

On February 13, 2026, the Bank of Zambia offered government bonds worth K4.2 billion across several maturities, ranging from 2 years to 15 years. Investors responded with bids totalling K21.3 billion, meaning demand was more than five times larger than what government initially planned to borrow. In financial terms, this is described as a heavily oversubscribed auction, and it is a strong signal of rising appetite for Zambian government securities.

To understand why this matters, it is important to first explain what the bond market actually is.

Government bonds are essentially a formal borrowing instrument. Instead of borrowing only from foreign lenders or printing money, the government can raise funds locally by selling bonds to investors such as banks, pension funds, insurance firms, and asset managers. These investors lend money to the State today, and government commits to repay it over time with interest. The bond market therefore becomes one of the clearest windows into investor confidence in Zambia’s economic direction.

The Bank of Zambia runs these auctions on behalf of government as part of domestic debt management. Investors submit bids indicating how much they want to invest and at what interest rate they are willing to lend. The Bank then accepts bids starting from the lowest interest rates upward until it reaches an amount it is comfortable borrowing. This is why the bond auction is not just about demand, but also about the cost of borrowing.

During last week’s auction, government did not take the full K21.3 billion offered by investors. It allocated about K9.8 billion, leaving more than K11 billion unaccepted. This was not a rejection of confidence. It was a pricing decision. Some investors demanded extremely high yields, and the central bank effectively drew a line to avoid locking government into expensive debt. This is part of what fiscal discipline looks like in practice: borrowing only at sustainable rates, even when demand is overwhelming.

The auction also showed easing yields on key long-term bonds. The 10-year yield moved down from around 17% levels into the 16.60% range, while the 15-year yield dropped closer to 17.59%. In bond markets, falling yields generally suggest improving confidence, because investors are willing to accept lower returns in exchange for perceived stability and reduced risk.

The bigger question is why investors are suddenly rushing into Zambian government paper at this scale.

Several macroeconomic conditions are beginning to align. Inflation has eased into single digits, falling from 11.2% in December 2025 to 9.4% in January 2026, according to official data. The kwacha has also strengthened compared to the volatility seen in 2024, supported by improved copper market performance and stronger external inflows. Zambia has also remained within its IMF-supported reform programme, which continues to act as an anchor for fiscal credibility in the eyes of markets.

Simply put, investors are responding to a perception that Zambia’s macroeconomic environment is becoming more predictable. Bond buyers do not chase uncertainty. They chase stability, policy consistency, and the belief that government will honour its obligations over time.

It is also notable that much of the demand came from longer-dated bonds, meaning investors are increasingly willing to lend to Zambia not just for two years, but for ten or fifteen years. This is not a short-term speculation. It reflects longer-horizon confidence in the country’s economic trajectory.

For ordinary Zambians, the bond market can feel distant. It does not immediately reduce mealie meal prices or transport costs. But it matters because government borrowing costs influence the entire financial system. When the State can borrow more cheaply, interest rates across the economy can gradually ease. Over time, this can support private sector credit, business expansion, and job creation.

This also reduces pressure on the national budget, leaving more room for social spending rather than debt servicing.

The February auction is therefore not just a technical event. It is a macroeconomic signal. It suggests Zambia is entering a phase where investor confidence is rebuilding, inflation pressures are moderating, and the domestic financial market is beginning to price the country differently than it did during the worst years of distress.

The challenge, as always, is transmission. Confidence at the bond auction must eventually translate into confidence in households, wages, and real economic relief. Markets may be forward-looking, but citizens live in the present. The task for policymakers now is to ensure that this stabilisation cycle reaches the real economy, not just the trading screens.

© The People’s Brief | Ollus R. Ndomu