HERITAGE | The Palace Coup That Shaped Barotseland’s Future

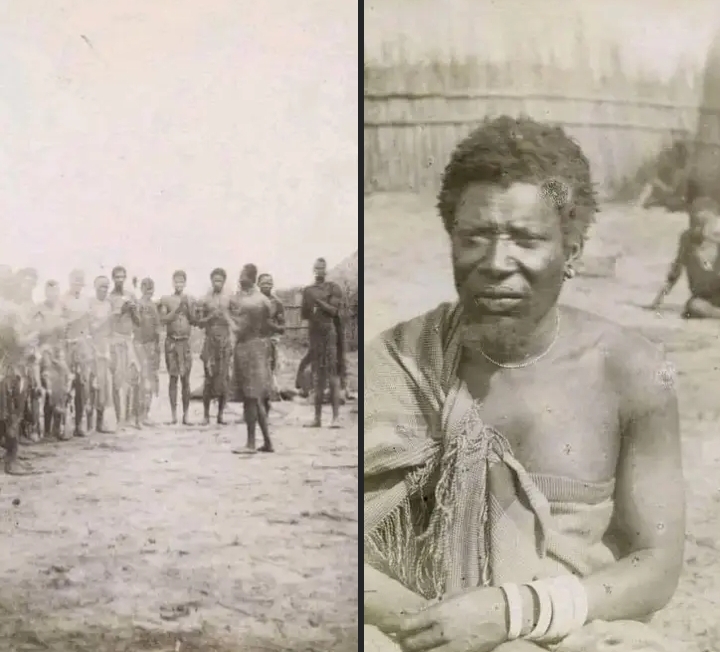

The figures in these fading photographs stand like guardians of a forgotten conflict. Manyengo tribesmen gather in a loose circle, their bodies marked by the dust of Lealui, their dance offered not to a celebrated monarch but to a contested ruler. The man they salute is Akufuna Tatila, a brief and troubled occupant of the Barotse throne.

His reign, framed by intrigue and unrest, lasted barely a year from 1884 to 1885. Yet it shaped one of the most dramatic political reversals in the history of Barotseland.

Akufuna’s rise followed a palace coup that stunned the kingdom. Lubosi, later known as Lewanika, had been forced into exile after being toppled by Ngambela Mataa. The new arrangement placed Akufuna, the son of Imbua, on the throne while his sister Maibiba was dispatched to Nalolo to balance the royal equation.

But behind the façade of order, the real authority remained in the hands of the Ngambela who saw in Akufuna a manageable figure rather than an independent Litunga.

The second photograph, more intimate and stark, reveals a man caught in demands beyond his reach. Akufuna could speak only Mbunda and could neither understand nor communicate in Siluyana or SiKololo, the principal languages of governance.

This linguistic barrier widened the gap between him and the Barotse aristocracy. It also exposed him to mockery and suspicion at a time when legitimacy in the Lozi state depended heavily on ritual speech, diplomacy and the ability to command loyalty across a vast territory.

Mataa soon lost faith in the very man he had elevated. Akufuna’s lack of authority and growing isolation threatened the Ngambela’s own grip on power. As frustration deepened, Mataa attempted to engineer another replacement, this time favouring Sikufele of Lukwakwa. Sensing danger, Akufuna fled first to Sesheke, then to the Batoka region, where he sought shelter among the people of Siachitema.

His short reign entered the historical record as an experiment in rule without cohesion and authority without a shared language.

While Akufuna drifted into the margins, Lubosi was gathering support. Some who had opposed him now viewed him as a stabilising force. Mambari slave traders, driven by commercial interests, joined his coalition after receiving promises of favourable terms.

At a time when the slave trade still operated in Barotseland, armed alliances shaped political outcomes and delivered influence to those who could negotiate both loyalty and violence.

Lubosi’s return was swift and uncompromising. The confrontation that followed ended with the deaths of Mataa, Silumbu, Numwa and Sikufele. Their fall cleared the path for Lubosi’s restoration in 1885.

He would rule as Lewanika I until 1916, guiding Barotseland through a period marked by centralisation, missionary presence and the early encroachments of colonial power.

These photographs, published in 1887 by François Coillard of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society, freeze the moment before that transformation. Coillard’s lens captured not only faces and gestures but a kingdom in transition.

The images stand as evidence of a political storm that reshaped Barotseland and defined the legacy of one of its most significant rulers. They tell us that history is not distant. It lives in the struggles, ambitions and fragile alliances that built the Zambia we know today.

: Supplied

© The People’s Brief | Narration —Ollus R. Ndomu; Editing —Lungowe Simushi