By Chaloka Beyani

(Professor of international law at the London School of Economics, member of the United Nations Fact Finding Mission to Libya, member of the United Nations Secretary General’s Expert Advisory Group to the High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, and former United Nations Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons. This article does not represent the views of the United Nations.)

The recent targeted extra-judicial killing of two civilians, Nsama Nsama and Joseph Kaunda, by the police on 23rd December 2020 are a culmination of a pattern of similar killings by the police, which have not been investigated or punished. That is the hall mark of impunity, understood as a persistent course of unlawful conduct in the knowledge that those involved will not be subject to legal consequences or punishment for killing others or violating their rights. I argue that in turn, this engages the responsibility of the Zambian state in international human rights law as well as entailing individual criminal responsibility in international criminal law for those connected to the killings within government and the police. This article explores these two issues in context.

The context that one discerns of the recent killings in Zambia from comparative international experiences is that of a country rapidly descending from the crest of democracy she straddled in 1991 to being a client state in the use of targeted killings, criminal violence and impunity. Professor Philip Alston, a former United Nations Special Rapporteur on Extra-Judicial Killing, defines targeted killing as “the intentional, premeditated and deliberate use of lethal force, by States or their agents acting under colour of law” and notes that in recent years, a few States have adopted policies, either openly or implicitly, of using targeted killings. Other techniques used among client states aim to close civic and political space, frustrate, harass, intimidate, subordinate, and subdue individuals and civilians into political submission for political ends.

Zambia’s astonishing descent from democracy to criminal violence must be prevented and contained by dealing with impunity. This requires holding the Government of Zambia’s responsibility for the violation of the human rights pertinent to the killings on the one hand, and on the other hand, establishing criminal responsibility individually for those connected with the killings under international criminal law, regardless of their official positions in the Zambian state as a way to address impunity. The most obvious human rights-based responsibility incurred by Zambia as a result of the killings is the breach of the right to life under the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of Zambia read, together with the relevant treaties or international agreements which are binding on Zambia, namely the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights 1981, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 1966.

The Bill of Rights under the Constitution of Zambia protects the right to life in Article 12(1): “No person shall be deprived of his life intentionally except in execution of the sentence of a court in respect of a criminal offence under the law in force in Zambia of which he has been convicted”. Contrary to this protection, targeted killings by police in Zambia have deprived victims of their lives intentionally in circumstances not involving the execution of a sentence following conviction by the courts. This is why the killings are classified as extra-judicial; they undermine the place and role of the Courts in our criminal justice system.

These killings violate Zambia’s international human rights obligations as expressed in Art. 6 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and Art.4 ACHPR of the African Charter on human and people’s rights. The basic protection lies in the prohibition on arbitrary/intentional deprivation of life, i.e., deprivation of life not in accordance with law or in violation of respect for life. In the case of Guerrero (Camargo) v. Colombia (45/1979), a woman was one of seven people shot dead by police in a house in Colombia in 1978. In its decision issued in 1982 the Human Rights Committee found that the police action “was apparently taken without warning to the victims and without giving them any opportunity to surrender…”, and it found “no evidence that the action of the police was necessary in their own defence or that of others, or that it was necessary to effect the arrest or prevent the escape of the persons concerned”. The Committee concluded that the police action “was disproportionate to the requirements of law enforcement in the circumstances of the case and that she was arbitrarily deprived of her life contrary to article 6 (1)” of the International Covenant.

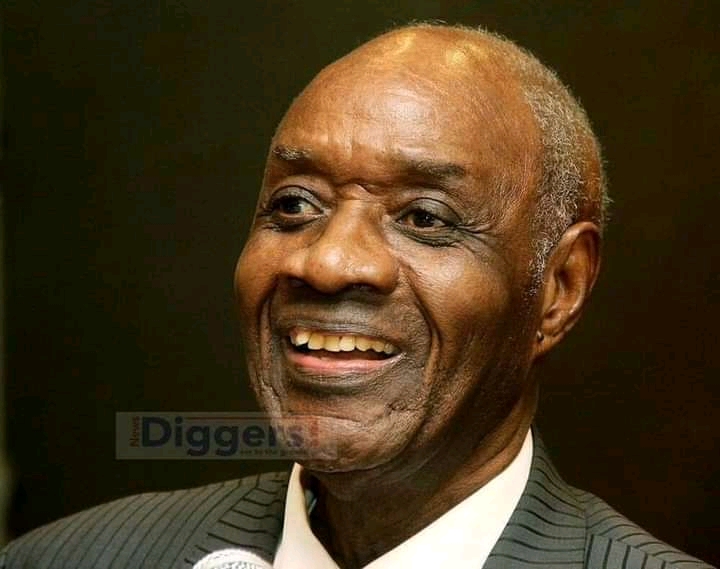

If Columbia seems distant, the case of Rodger Chongwe v Zambia (821/1998) echoes the current targeted extra-judicial killings, arising as the case did, from an incident of Zambian police shooting at and injuring Dr Rodger Chongwe and former President Dr Kenneth Kaunda in Kabwe in 1997. In its decision, the Committee observed that “article 6, paragraph 1, entails an obligation of a State party to protect the right to life of all persons within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction. In the present case, the author has claimed, and the State party has failed to contest before the Committee that the State party authorised the use of lethal force without lawful reasons, which could have led to the killing of the author. In the circumstances, the Committee finds that the State party has not acted in accordance with its obligation to protect the author’s right to life under article 6, paragraph 1, of the Covenant”.

An extra-judicial killing may also take place in circumstances of where a convicted person engages regional or international human rights bodies but is executed before such bodies complete hearing of the case. This was the decision of the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights in International Pen and others on behalf of Ken Saro-Wiwa v Nigeria (161/97 (1998) concerning the politically driven execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa, a political leader of the Ogoni people in Nigeria who was executed secretly.

Protection of the right to life carries negative obligations (constraint) to not take life arbitrarily/intentionally, and specific positive (proactive) obligations arising from the general duty to protect, inclusive of the scope and quality of protection. An underlying test to both obligations is the foreseeability of the risk that killing that must be avoided. The foreseeability of risk was breached when the police discharged firearms with live ammunition into a peaceful crowd, resulting in the killing of Nsama Nsama and Joseph Kaunda.

Significantly, the right to life also enshrines procedural obligations, which in the context of killing by police or security forces, make it mandatory to hold a public inquiry about the circumstances of the killing and to seek to identify the killers, as first established by the European Court of Human Rights in Mc Cann v UK following the killing of terrorist suspects in Gibraltar. Such decisions are significant for the fact that the Bill of Rights in the Constitution of Zambia was extrapolated from the European Convention on Human rights 1950.

In Rodger Chongwe v Zambia, the Human Rights Committee similarly remarked that “in the present case, it appears that persons acting in an official capacity within the Zambian police forces shot at the author, wounded him, and barely missed killing him. The State party has refused to carry out independent investigations, and the investigations initiated by the Zambian police have still not been concluded and made public, more than three years after the incident. No criminal proceedings have been initiated and the author’s claim for compensation appears to have been rejected. In the circumstances, the Committee concludes that the author’s right to security of person, under article 9, paragraph 1 of the Covenant, has been violated.” Thus, the procedural guarantee obligation to hold a public inquiry is different from an inquest and an internal administrative inquiry into the conduct of the police as ordered by President Lungu. The inquiry must be independent, held in public, and its findings must also be made public for reasons of transparency and accountability.

Apart from the right to life, there are other related rights violated. Targeted extra-judicial killings amount also to torture and other cruel, or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which is absolutely prohibited. Such killings are calculated to hinder freedom of peaceful association and assembly, and freedom of movement, thereby impeding the enjoyment of these freedoms. A case for individual smart sanctions against those involved in extra-judicial killings and repression of human rights and democracy must be considered by other concerned states and institutions to give full effect to the individual responsibility to not violate human rights, as everyone has a right and a duty to defend the Constitution (Art 2) and therefore the Bill of Rights in it.

Turning to the case for individual criminal accountability, it is clear that murder is a crime punishable under the Zambian Penal Code (S. 201). Targeted extra-judicial killings by police epitomise the criminality of the state and undermine the judiciary. Establishing individual criminal responsibility for those responsible nationally or internationally therefore serves to ‘decriminalise’ the state by identifying and prosecuting those responsible. Equally the failure to do so reinforces the criminality of the state itself. A major problem here is that the public order system overseen by the police has lost its legitimacy to the detriment of the effectiveness of criminal justice in Zambia.

Normally, police are an important part of the public order and criminal justice system. Targeted extra-judicial killings by the police, including of a national prosecutor, selective politically induced arrests, are factors that have contributed to the erosion of the legitimacy of public order and criminal justice in Zambia. Citizens have lost trust and confidence in the police and are wary that far from protecting them, the police are bent on disenfranchising them politically and socially. The long-term consequence of this will be dysfunctionality and disorder in criminal justice. That will breed chaos and instability, which in my experience is easier to prevent, but difficult to contain or redress unless the offending elements are rooted out of the system followed by timely remedial participatory and inclusive measures taken nationally on a parity of esteem among Zambians. At any rate, a vetting of the police involving background checks on them, their conduct and suitability to remain in the police, their ability to protect and safeguard the public, and to discharge police functions professionally, is inevitable.

In a globalised world, when national criminal justice systems and mechanisms are unable or unwilling to establish responsibility for the accountability of the architects of criminal violence recourse is to be had to international mechanisms of accountability. The International Criminal Court (ICC) was created for this role and its complementary jurisdiction rests on this premises. The Court was established ‘to put an end to impunity for the perpetrators of these crimes and thus to contribute to the prevention of such crimes.’ Zambians had the wisdom to affirm Zambia’s continued membership of the ICC in 2017 during consultations held by the Government when the question whether Zambia should disengage from the ICC arose, which gives the Court a great measure of standing to monitor and engage with the current situation in Zambia.http://www.parliament.gov.zm/…/Report%20on%20the%20ICC…

Informed by the definition of targeted extra-judicial killing, the seemingly pre-meditated or organised and lethally executed killings point to crimes against humanity (Art 7 Rome Statute). To the extent relevant to the Zambian context, these include murder, torture, extermination, persecution, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law, and other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health. Attention is drawn to the Auschwitz Institute for the prevention of genocide and mass atrocities recent report of June 2020 on Supporting the Prevention of Identity-Based Violence National Mechanisms: A Case Study of Zambia

http://www.auschwitzinstitute.org/…/Zambia%20Case…

From the onset of the Nuremberg Trials of major Nazi war criminals in 1945, it is in the 1990’s that trends in international criminal law have developed. As shown in the decisions of the Yugoslav Tribunal in the cases of Tadic, Milosevic and Blaskic, and the decision of the Rwanda Tribunal in the case of Kambanda, these developments are such that Head of State immunity is no longer applicable before international criminal tribunals. Article 27(1) of the Rome Statute establishing the ICC consolidated these developments into the following principle: “This Statute shall apply to all persons without any distinction based on official capacity. In particular, official capacity as a Head of state or government, a member government or parliament, an elected representative or a government official shall in no case exempt a person from criminal responsibility under this Statute, nor shall it, in and of itself, constitute a ground for reduction of sentence.”

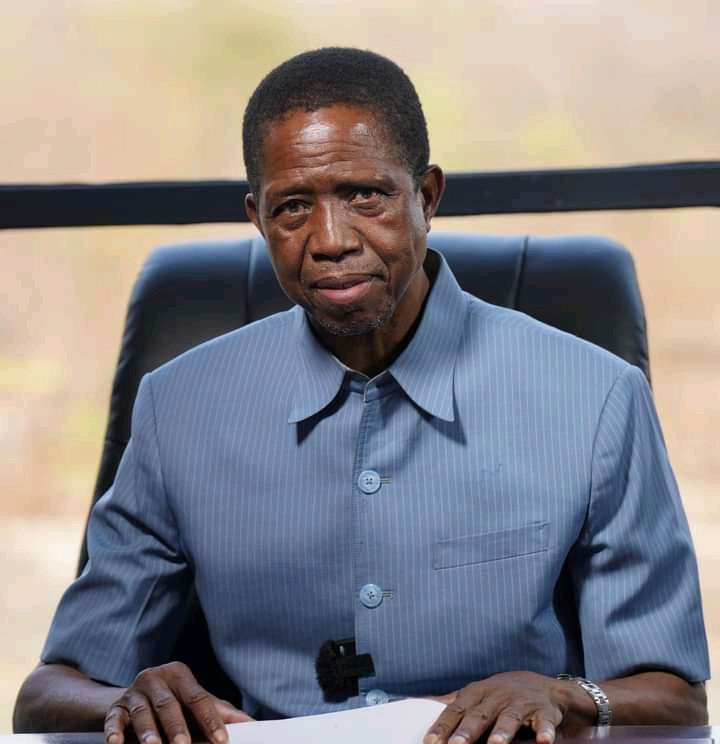

This means that President Lungu can be indicted and prosecuted by the Court for his actions or omissions constituting crimes falling within the jurisdiction of the Court because he is constitutionally designated as the Commander-in-chief of the Defence Force (Art 91(1)), of which the police are a component. The fact that the President enjoys immunity under the Constitution is irrelevant. According to Article 27(2) of the Rome Statute: “Immunities or special procedural rules which may attach to the official capacity of a person, whether under national or international law, shall not bar the Court from exercising its jurisdiction over such a person.” For good measure the South African Constitution 1996 makes no provisions of the President as Commander-in-Chief or of presidential immunity.

In so far as the prosecution of Presidents is concerned, Laurent Gbago, the former President of Ivory Coast was the first one to stand trial before the ICC in 2011. He was convicted initially, and subsequently acquitted in 2019 of crimes against humanity in the 2010 post-election violence. In 2012, I investigated the violation of the human rights of internally displaced persons in Ivory Coast who had been displaced by post-election violence and gained insights at first hand on the nature of the violence in there. Not far from us, President Kenyatta of Kenya had been indicted by the ICC in connection with post-election violence in 2007-08 prior to his presidency but charges against him were dropped in 2014. In Kenya I was first involved as a member of the Committee of Experts that drafted the 2010 Constitution that was crafted to be a remedy against the scourge of violence, but later I also investigated the 2007/2008 post-electoral violence that led to massive displacement as Special Rapporteur in 2012.

Both Ivory Coast and Kenya had experienced post elections patterns of ethnic violence that resulted into thousands of killings and massive internal displacements. Dimensions of this kind of violence, triggered by police killings, is manifesting itself in Zambia in the period leading up to the 2021 elections. This in a country that has had no history of such violence before. The hand of the client state is at play, and as elections in Africa have become a ‘do or die’ affair for incumbents, it is imperative that the ICC engages with the situation in Zambia well prior to the elections as a preventive and deterrent measure in order to establish early criminal responsibility for the architects and perpetrators of the violence.

Although former President Gbagbo was acquitted, and charges against President Kenyatta were dropped for lack of evidence, their appearance before the Court is a warranted reminder of the individual accountability of those who lead states because the primary responsibility for preventing and stopping the violence rests upon them. Former Liberian President Charles Taylor was convicted in 2012 by the Special Court for Sierra Leone and sentenced to 50 years for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other serious violations of international humanitarian law. More recently in 2016, the former President of Chad, Hissen Habre, was convicted by the Extraordinary African Chambers’ Special Tribunal in Senegal, becoming the first former President to be convicted in Africa for crimes against humanity, war crimes, torture, sexual violence and rape. Thus, in addition to the ICC, special mechanisms can also be set up to try international crimes at the highest levels. In the case of Zambia, the message to be heeded is that no one is immune, and no one is exempt from the International Criminal Court, if they have committed crimes that are punishable by the Court.

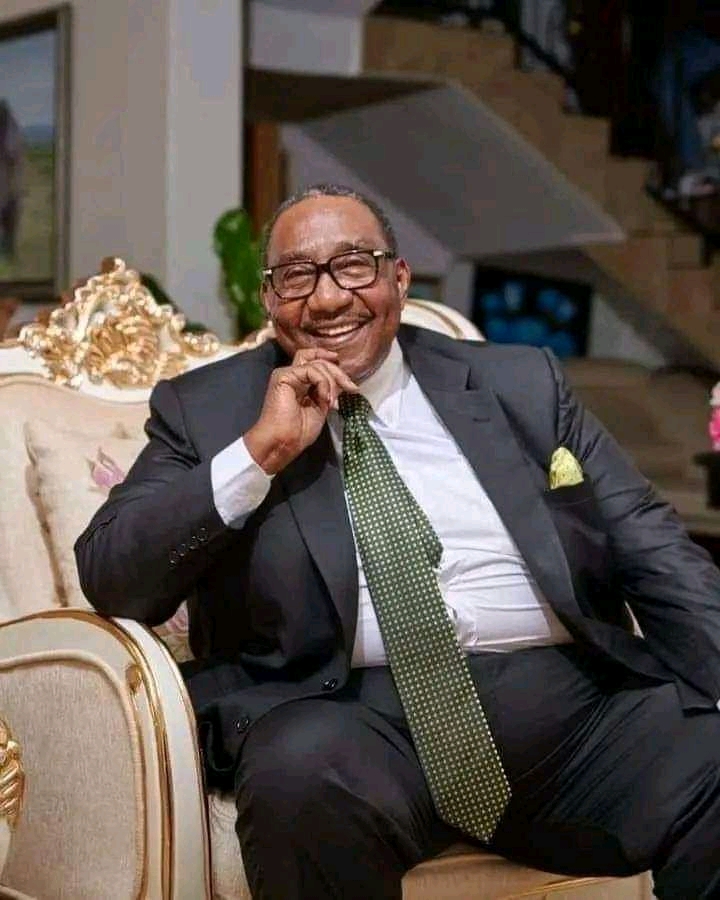

In addition to President Lungu, others that risk indictment by the ICC include the Home

Affairs Minister Stephen Kampyongo who is in charge of the police, other Ministers or officials involved in decision making that led to the killings, the Inspector General of Police Kakoma Kanganja and the police command structure, and the actual operatives. For the latter and others, the defence of acting under superior orders that involve international crimes such as crimes against humanity is not open to them, so all should think carefully before executing orders that will implicate their being prosecuted before the ICC. A safe protective practice is to request any such orders to be made in writing by those who make them. Other states are also willing to invoke universal jurisdiction to arrest and try identified perpetrators before their Courts when they travel abroad. A case in point is that of the late former leader of Chile, General Pinochet, who was arrested on a shopping trip to London upon a Spanish request for his extradition. The report on universal jurisdiction on the link below was drafted by a group us acting officially as expert advisors to the African Union and the European Union in 2009: http://africa-eu-partnership.org/…/rapport_expert_ua…

However, as in any prosecution, the key issue is evidence, which is why it is important to document all available evidence, including statements made. International Courts now also allow the submission of credible digital and electronic evidence, such as videos taken. Sophisticated means of collecting evidence have also been formulated, such as remote sensors, satellite imagery that would capture the movement, position and deployment of the police and other security forces. More advanced tools are specially programmed web-crawling algorithms, and a combination of video, photographic, text, and media platforms. In short, modern evidence gathering techniques are such that there is nowhere to hide for the perpetrators of criminal violence, brutality, and impunity.

Finally, about crossing the rubicon. In 49 B.C. on the banks of the Rubicon river, Julius Caesar faced a critical choice. To remain in Gaul meant forfeiting his power to his enemies in Rome. Crossing the river into Italy would be a declaration of war. Caesar chose war. Jesus retorted, “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s”. (Matthew 22:21).

Leave a Reply