By Field Ruwe, EdD

PLEASE NOTE: I am an academic, not a politician, and do not envision myself as having a political career. This is a thoroughly researched piece of work, not an opinion editorial. You have to read the entire article to fully comprehend its content.

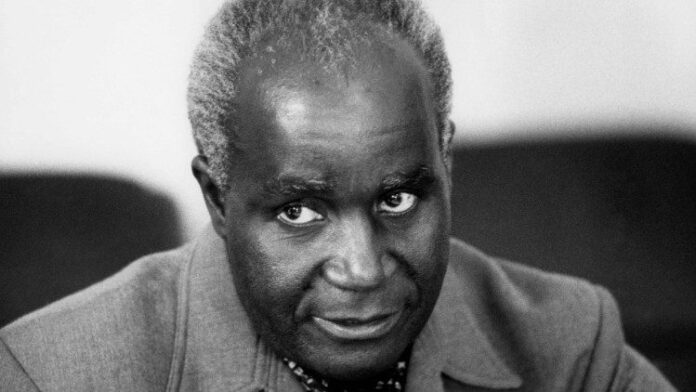

On July 12, 1966, Chancellor of the University of Zambia, Kenneth Kaunda, spoke: “I have to reiterate on this most important occasion what I have already said in the past, that as far as education is concerned, Britain’s colonial record is most criminal. This country has been left by her as the most uneducated and the most unprepared of Britain’s dependencies on the African continent. This record is even treasonable to mankind when it is recalled that in the seventy years of British occupation, Zambia has never lacked money, and, except for a year or two, her budget has never been subsidized by the British Treasury.”

The occasion was the official opening of the University of Zambia. The above quote was Kaunda’s scathing rebuke of Britain’s failure to develop a robust educational system in Northern Rhodesia. In January 1964, the then Prime Minister Kaunda had received the controversial 1963 Lockwood Report on the establishment of the University of Zambia.

In planning the establishment of the University of Zambia, the Lockwood Committee recommended that the proposed University of Zambia entrance requirements be a “lower level than was the norm in Africa” [see Report on the Development of a University in Northern Rhodesia, 1963]. This decision can be grandfathered into the University of Zambia’s degree deemed as inferior by the UK NARIC recognition agency.

It is imperative to keep a sense of historical perspective to fully understand where I am headed with this. Between 1890 and 1925, the absence of a defined educational policy in Northeastern Rhodesia and Northwestern Rhodesia, established under the British South African Company, was due to Cecil Rhodes’ opposition to educating natives. Consequently, Rhodes refused to create a budget for the education of indigenous people in the two territories. It was Rhodes who inserted words like “inferior,” “primitive,” and “backward,” in the “othering” language that white settlers perpetuated and Queen Victoria failed to condemn.

Upon the British government assuming control of the two regions and establishing Northern Rhodesia in 1925, the American Phelps-Stokes Commission was formed with the aim of developing an education system suitable for the local inhabitants. The commission advocated for the training of Northern Rhodesia’s indigenous population in skills like manual labor and craftsmanship, instead of establishing Western-type schools like was the case in other British territories in Africa. Similarly, the British implementation of the education system for indigenous inhabitants of Northern Rhodesia between 1925 and 1964 aimed to align with many of the proposals put forth by the Phelps-Stokes Commission.

Apparently, the Lockwood Committee chaired by Sir John Lockwood, former Vice Chancellor of London University, was aware of the Phelps-Stokes Commission’s recommendations. Conceived out of a conference on the Development of Higher Education in Central Africa, held in September 1962, at Antananarivo, Malagasy, the Lockwood Committee was tasked with the establishment of a university in Northern Rhodesia.

The then Minister of Local Government and Social Welfare, Kenneth Kaunda, was hoping the proposed Zambia University (University of Zambia) would replicate the educational models of Makerere University (Uganda), Dar-es-Salaam University (Tanzania), University of Nairobi (Kenya). These institutions like the others in the British colonies in Africa mirrored the higher education system of Great Britain and held affiliations with the University of London.

Between 1946 and 1970, the University of London engaged in collaborative efforts referred to as “schemes of special relations” with universities in the Commonwealth. Such institutions were conferred a royal charter which granted them specific privileges. The charter, signed by the Queen of England, enabled colonial universities to align with the University of London on matters such as student admission criteria, course content, examination procedures, and academic affairs.

Imbued in the British imperial doctrine of keeping the indigenous people of Northern Rhodesia at the bottom of the totem pole, Sir John Lockwood, a former Vice Chancellor of the London University, made no effort to enroll the University of Zambia into schemes of special relations with the University of London. Instead, the Lockwood Committee deviated from the British education model and made the University of Zambia autonomous, as opposed to a university benefiting from the British education system.

Kaunda was fully aware of this. After completing his studies at Munali Central Trade School in 1941, Kaunda acknowledged the importance of acquiring a British education. The British Department of Education had imposed the British system of education and their language on their colonies. As education began to occupy a prominent position in the consciousness of the indigenous inhabitants, the desire to learn English and attend British schools surged.

Bearing this in mind, Kaunda, who assumed office as republican president on October 24, 1964, was infuriated upon learning that the Lockwood Commission had excluded Zambia from the schemes of special relations. He became even more outraged when he discovered Zambia was the only country in the Commonwealth omitted. Dissatisfied with the Lockwood Report, Chancellor Kaunda contemplated the rationale behind the unjust treatment that Her Majesty’s most affluent African territory had endured in its educational history. He could not help but to suspect an element of racism in the decision-making process.

In the scholarly paper titled “Education in Zambia: Qualitative Expansion at the Expense of Qualitative Improvement,” J. Elliot sheds light on the intentional racist actions taken by colonial masters and white settlers in Northern Rhodesia to impede the educational advancement of indigenous people in Northern Rhodesia. According to Elliot, the underlying motivation was driven by self-interest and the desire to secure own employment and uphold a system that kept the native population uneducated and limited to menial jobs.

Elliot’s supposition was reflected in the Lockwood Report that set out to keep the indigenous people in an inferior status by recommending a University of Zambia of a lower caliber compared to other universities in the Commonwealth. The Lockwood Committee, in its recommendation, proposed that the University of Zambia should have admission criteria that were relatively lower compared to other African and colonial universities.

The committee provided a rationale for its decision by referencing the limited number of “A” level Form Six graduates and asserting that exclusively admitting them to the University of Zambia would restrict academic prospects. The committee further recommended that achieving a specific standard of performance in the “O” level of the G.C.E. examination should be the basis for admission into degree programs of the University of Zambia. This marked a stark departure from the usual practice in the Commonwealth of Nations, in which university admission typically necessitated “A” levels.

On independence day, the Kaunda government encountered a significant dearth of human resources, as there were only one thousand indigenous Zambians possessing school certificates and a mere one hundred university graduates who had schooled abroad. With this, Kaunda, in need of rapid acceleration, failed to condemn and challenge the recommendations of the Lockwood Committee. In 1965, Kaunda went ahead and commissioned the building of the University of Zambia on Great East Road as recommended by the Commission.

The following year, the University of Zambia admitted 233 degree students, with the highest degree available at the time being a Bachelor’s. Among the total student population, 204 students with “O” levels were required to take a year of “A” levels, while the remaining 29 students who already had “A” levels were able to enter directly into the second year of studies. As a result, the first cohort of degree students completed a two-year program and earned a comprehensive four-year degree upon graduation, while “A” level students took three years to complete their studies.

In 1967, the University of Zambia provided equal opportunities for degree examinations to external candidates, without any distinction in the qualifications obtained. The imposition of this proposal, supposedly in response to the Zambian government’s request for skilled labor, ultimately led to a further reduction in quality standards. Furthermore, standards were diminished when the Committee suggested the introduction of correspondence studies.

The historical context outlined in this article reveals that UNZA was established not with the intention of conforming to global standard, but rather to addressing the specific requirements of Zambia. Consequently, the university continues to struggle to achieve its intended roles as a prestigious educational institution, a repository of knowledge, and a hub of innovative research.

As long as the University of Zambia maintains its status quo, the UK NARIC evaluation that has bedeviled the UNZA graduate and degraded his/her degree to an inferior diploma level will maintain the stigma.

The most serious obstacle to the growth of the university is its reluctance to jettison the Lockwood recommendations and embrace a universally accepted dynamic ecosystem that spurs sound and relevant academic programs. It is the opinion of this author that the university should no longer draw its inspiration from the local environment but from those universities around the world that have created educational systems that yield positive outcomes.

The rights to this article belong to ZDI (Zambia Development Institute), a proposed US-based Zambian think tank. On May 19, 2022, a comprehensive proposal was delivered to President Hichilema through Principal Private Secretary Bradford Machila. Author Dr. Field Ruwe holds a Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership. He is affiliated with Northeastern University, Boston, MA, US.

A shaming article. The real question is why still having colonial education as a reference point, if Zambia had people who were ‘so called educated’? It is therefore laughable to hear people calling themselves ‘ learned colleague’, or putting titles after their names yet nothing substantive comes out it for Zambia to be a true force academically etc as the author has pointed out.

Why should we use everything European and nothing authentically ours. Why covering wigs in courts, using Roman, Dutch and British lawys etc when we could have used our better systems. Africa had no prisons before the colonialists yet offenders were delt with. Gacaca in Rwanda resolved a lot of the issues much better than the Western system. Many African Governance systems – bottom up decision system, are much superior to the so called democratic system which only cause tension in society. An example of this is the Luyana or Lozi system. Many other African systems are like that. My take on this is to ‘ develop our better systems.

Ok in my time (1996), twale joba just to get yourself a slot at Unza or Cbu. And when you go ku university tatwalelela unless we were learning fake things. I dont know about abaiche ba nomba