The Birth of a Nation (1890-1911)

By Amb. Emmanuel Mwamba

Part II

TROUBLE WITH THE LOCHNER CONCESSIONS

The celebration of the signing of the Lochner Concession was shortlived.

Rev. Coillard was a trusted confidante of the royal court and the royal family, and who was doing the detailed interpretation to the terms of the Agreement.

His failure to notice that the men were not from Britain or the High Commissioner’s colonial office in Cape Town, but from a team from a private company, became a highly regrettable and historical error.

The Lochner Concession instead of offering and guaranteeing a British Protectorate, were in fact, seeking exclusive exploration and mineral rights, and land appropriation and concession.

The Concession signed gave away large territories beyond the reign of the Kingdom.

The Concession was similar to the Rudd Concession with Lobengula, where the BSAC signed the Rudd Concession with King Lobengula for exclusive and open-ended mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and other adjoining territories.

Upon discovery of this, Rev.Coillard regretted hosting Lochner as a broker and interpreter for his BSAC entourage.

Frank Elliot Lochner, Alfred Sharpe and Joseph Thomson were sent to these territories by Cecil Rhodes to negotiate treaties that would secure mineral wealth and land rights from potentates in their respective principalities offering British(BSAC) protection in return.

Yet Lochner and his men had no authority or jurisdiction to make treaties on behalf of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.

Rev. Coillard wrote to Rev. J. Smith; “Lochner exploited my generosity which my vocation imposes on me and exploited my hospitality”.

Lochner also confirmed Coillard’s feelings in a letter to a Mr. Harris, “I am sure the BSA Company owes much to Mr. Coillard than to myself in having secured the Barotse Country”.

Another person who opposed the Lochner Concession was a young Englishman, George Middleton, a lay helper at the Paris Mission Society until 1887 and turned ivory trader.

He called it “an immense sale of the country”.

He advised King Lewanika to write a protest letter and repudiate the concession to Lord Salisbury, the Prime Minister of Great Britain.

The letter was written to the Prime Minister and a demand to disavow it. Part of it read:

“He (the King) states that the objects of the Company were not explained at the same time as they were written in the document purporting to be the Concession as agreed upon.”

“The King is very indignant at the sweeping nature of the agreements, and the very exclusive terms of the rights to have been conceded by him to the Company, and further states that he repudiates the document in question in its entirety, as he didn’t understand the meaning of the document”.

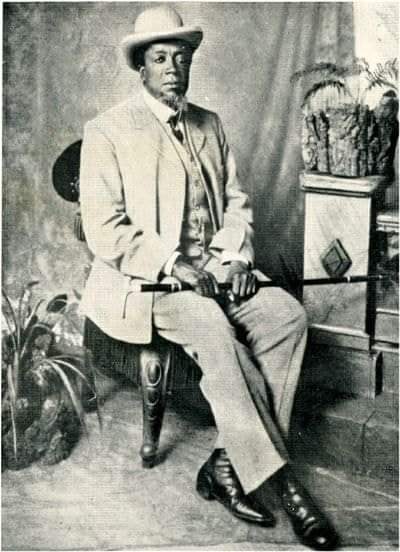

Another missionary, James Johnstone, a photographer, medical doctor and explorer from Jamaica took six Jamaicans on his journey to cross central africa from west to east in the footsteps of David Livingstone.

He arrived in Mungu on 3rd December 1890 and was hosted by Rev. Colliard at the Barotseland Mission at Sefula.

On new’s year day on January 1891, Johnstone’s party witnessed a religious occasion deemed to be Zambia’s first white wedding ceremony.

King Lewanika’s son, Litiya was getting married to Katusi.

Tables and Chairs were set.

The high table was set to include King Lewanika, his wives, his sister, Mukwayi.

Johnstone stated that King Lewanika could not be allowed by his Indunas to sit at the high table as it had women and the chair set for the bride was empty as she refused to sit on it.

Johnstone claimed that the bride had never sat on a modern chair, but infact it was a traditional act of reverence in the presence of husbands, for the wife to sit on the floor.

His diary recorded that Johnstone arrived on 3rd December 1891. Johnston’s party were offered free shelter by King Lewanika.

Johnstone states that King Lewanika told him how he had written to the British asking that his kingdom should be made a British Protectorate.

He had waited for years for a reply and then men had arrived with papers claiming that they had the power to make this happen.

The King was reassured as the local missionary, Monsier Coillard, who was his interpreter at the meeting, and the King was reassured by Coillard’s confidence in these men.

Lewanika had been thankful that his wish had been granted and he had sent two enormous elephant ivory tusks as a present for Queen Victoria.

Lewanika was incensed to find that the men were from a South African company and that the ivory tusks were not with Queen Victoria but probably as ornaments in an office room.

Johnstone also assisted King Lewanika to write another letter of protest.

Lewanika was to prove a great help to Johnstone as he was able to command assistance for Johnstone, from nearby subordinate chiefs on his journey.

READING AND REFERENCES

1. Collective Responses to Illegal Acts in International Law: United Nations, By Vera Gowlland-Debbas

2. “Reserved Area: Barotseland of the 1964 Agreement,” Zambia Social, by Bull, Mutumba Mainga (2014) Science Journal: Vol. 5 : No. 1 ,

Article 4.

Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/zssj/vol5/iss1/4

3. The Elites of Barotseland, 1878-1969: A Political History of Zambia’s, by Gerald L. Caplan

4. Robert Thorne Coryndon: Proconsular Imperialism in Southern and Eastern, By Christopher P. Youé

5. Barotseland’s Scramble for Protection, by Caplan, G. (1969).

6. The Journal of African History, 10(2), 277-294. doi:10.1017/S002185370000952X

7. Journal of Museum Ethnography by Margret Carey

8. No. 15, Papers Originating from MEG Conference 2002: Power and Collecting, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh (March 2003), pp. 1-7

9. The Battle for Control of the Camera in Late Nineteenth Century Western Zambia by Gwyn Prins

10. African Affairs,

Vol. 89, No. 354 (Jan., 1990), pp. 97-105

11. White Induna: George Westbeech and the Barotse People by Richard Sampson

12. Before the Rise of the Modern Copperbelt 2017

By Mwelwa C. Musambachime

13. Barotseland’s Scramble for Protection

Gerald L. Caplan

The Journal of African History

Vol. 10, No. 2 (1969), pp. 277-294

Published by: Cambridge University Press

https://www.jstor.org/stable/179515

Page Count: